Screening Tools for FASD

Screening tools have been developed for under 18s and over 18s. These documents have not been developed through Universities but have been the result of 16 years’ experience along with the experience of other caregivers and professionals who have had input into this document. They have been sent to the United States for validation. The completion of either of these forms will assist in a diagnosis.

![]() FASD Screening Tool – over 18.pdf779.93 KB

FASD Screening Tool – over 18.pdf779.93 KB

![]() FASD Screening Tool – under 18.pdf702.01 KB

FASD Screening Tool – under 18.pdf702.01 KB

Identifying Individuals with Prenatal Alcohol Exposure

Developed by NOFAS – www.nofas.org

Most children diagnosed with fetal alcohol-related problems are not identified before they reach school age, when they are referred for a learning disability or an attention deficit disorder. If clinicians can identify alcohol-related effects early, intervention approaches can minimize the potential impact of these effects.

Clinicians who see young children for routine well-child care have a special opportunity to identify children exposed to alcohol. They may want to ask the caregiver bringing a child into the clinic about alcohol exposure during pregnancy. It is important to frame these questions in the context of the overall health of the child.

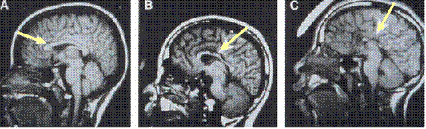

The brain of a normal individual (A) and two with FAS (B,C) shows permanent loss of the tissue indicated by the arrows (portions of the corpus callosum).

The impairments associated with FASD are often a reflection of underlying structural changes in the brain, as evidenced above by changes in the corpus callosum. An MRI might also reveal decrease in brain size, damage to the basal ganglia, or reduced size of the cerebellum.

If the birth mother brings in the child, clinicians may want to start by asking about her current alcohol use before asking about alcohol use during pregnancy. Women are willing to talk about this issue if it is presented with a caring, nonjudgmental approach.

If the father brings in the child, clinicians may want to ask about the mother’s use of alcohol currently and during pregnancy. It is important to tell the father that this is routine with every patient and is important for the best care of the child. The father may have helpful insight into the alcohol use of the mother.

If a foster parent or other caregiver brings in the child, clinicians may want to ask if the caregiver has any knowledge of the birth mother’s alcohol use during pregnancy. It is always important to be tactful and sensitive when asking for this information. Stress that this information is for the child to receive quality health care and it is routine to ask these questions.

Information for Health Practitioners is from the Telethon Insitute for Child Health Research

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

ADHD and FASD

Sometimes our children are diagnosed with ADHD as well as FASD. Here are some ways to help your child if he or she has been diagnosed with co-morbid ADHD:

ADHD: Talking to Your Child’s or Teen’s Teachers

This printable guide offers suggestions on how to approach educators about your child’s ADHD.

Creating a Comfortable Home Environment for Children with ADHD

This guide has a wealth of information on how to support your child at home by fostering a calm, soothing environment.

If you suspect you have ADHD, this resource provides excellent information on factors your doctor considers in diagnosing you, as well as some of your treatment options.

How to Succeed in the Workplace with ADHD (American)

This guide not only outlines your legal rights at work, but also provides tips for accomplishing your career goals despite your ADHD.

For adults and children alike, there are an array of activities to try that can help ease ADHD symptoms

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

What doctors and providers can do

I have been to many doctors and service providers over the years. It doesn’t take much insight to recognise that the job of ensuring the health and wellbeing of clients and patients must be rewarding, frustrating, fascinating and heartbreaking. Without people willing to do this job we would all be in an appalling situation. Can you imagine having to parent a child with a disability without the support and wisdom of your health professional, or in fact, without any support at all?

Unfortunately, that very thing has been happening for one group of people and at least one disability. They are the families living with FASD. It’s hard to say why our professionals and policy makers didn’t identify this condition years ago. When Canada and the United States started working on research and then diagnosis decades ago, we should have been on to it then.

But it seems that FASD has slipped by Australians undetected either intentionally or unintentionally when Canada, New Zealand, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa and even Russia all seem to be more aware of the needs of this cohort than Australia. Recent research from Western Australia highlights the huge gap between health professionals and their knowledge of this condition. This research found that only 12 percent of medical practitioners in Western Australia could identify all four diagnostic criteria for full FAS and only 2 percent felt prepared to deal with it[1]. In the study they say there is no reason to suppose these figures are any different in other states and territories.

When you go to your health professional you expect them to have the knowledge they need in order to help you. If they don’t, then they refer you on. In Australia there are few doctors and providers who really understand FASD, more who understand a little and many who say they understand but really don’t − and at the time of writing only one specialist referral option for treatment and management for young children in Queensland and several in Western Australia.

Most of us think of the Hip

pocratic Oath as advising doctors to be careful what they do and if there is no option for improvement, then at least ‘do no harm’. I think of the Hippocratic Oath in terms of FASD in a different way. I feel that doctors who do nothing to assist a child with FASD or parents who come to them for advice as doing harm by doing nothing to help. And that’s how it is in the majority of rooms around Australia judging by the comments from parents in the rffada caregivers’ group on Facebook.

Over the last fifteen years, the situation that has consistently proved to be the most challenging for parents has been trying to find a service provider, medical professional or anyone who knows about FASD, who is prepared to talk to parents about it, and who can provide the support, information and referral options.

I could never understand why doctors were so noticeably reluctant to talk to me about the possibility of my son having a FASD. With a little more insight and after many conversations, it seems that they might have taken this position with the misunderstanding they were saving me from pain by minimising the problems associated with FASD or because they believed nothing could be done about his brain injury.

Not being able to talk to a doctor about my fears, particularly about the possibility of my son ending his life was quite dangerous for Seth and terribly hard for me. Additionally, the misunderstanding that nothing can be done defies a variety of evidence and wisdom-based interventions and accommodations from overseas. If appropriate strategies can be implemented at home as early as possible, and all are aware that the child has FASD, some secondary disabilities may be avoided.

Appropriate strategies for people with FASD are different to those at home, school, in employment and in society to those with, say, Autism or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [ADHD] both of which, to most people, are more a more acceptable diagnosis than FASD where there is a direct causal link. This is a very important lesson I learnt when I went to my first doctor about Seth’s behaviour. At first I believed that because the doctors did not seem concerned, then my concern was misplaced. It was only after attending one of the North American conferences that I began to see just how pivotal an accurate diagnosis and a management plan would be.

As a mother who cares deeply about her children, I can say with confidence that while discovering that I had physically harmed my boys was a very difficult time for me and one that could have easily destroyed me, having an explanation for their idiosyncrasies and behaviours was a relief.

So while doctors and other professionals might be right in their belief that the effect of diagnosing FASD would be a disturbance to the family, it is a responsible disturbance, and one which they must be prepared to make. At the very least they must have a comprehensive discussion with the parents, remembering that a diagnosis prior to age six can help mitigate some of the secondary disabilities such as mental health and substance use problems which are often worse than the primary disability.

I am not particularly fond of ‘if onlys’ but I have to repeat this one because it’s one of the two that I try not to think of on a daily basis. If only my obstetrician had told me that alcohol was a teratogen and therefore a grave danger to my children, our whole family would be in a very different position. As a matter of absolute urgency, doctors in Australia should be educating themselves on the problems associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. With new research into epigenetics, geneticists have found that while FASD itself is not carried down to subsequent children unless alcohol is consumed prenatally, epigenetic effects can be.

So doctors, please talk to your patients about alcohol and pregnancy and advise them that abstinence is safest for their baby. When they ask if a couple of drinks will be safe, tell them that alcohol is a teratogen – a substance that is known to cause birth defects. If they persist, tell them that children with FASD are so difficult to parent that marriages can break down, parents can break down and children often have to be fostered out. Advise them that the sooner they stop drinking the healthier their baby will be.

For a mother who is a social drinker it may need only a confirmation that alcohol is harmful. That may be all it would take to save a child from a dreadful disability. Queries about the drinking habits of all female patients of child-bearing age whether pregnant or not, should occur during any consultation. It should become a standard enquiry or educational message when discussing birth control, safe sex or preparing for pregnancy, because drinking in the early stages of pregnancy [during the period of pregnancy called gastrulation] is likely to result in full FAS where the facial features are present.

Please don’t be silent when a mother brings to you a child she suspects of having FASD. Would you be silent if your patient had diabetes? Would any medical person knowingly place a child at risk by not giving him every chance of alleviating the symptoms of his condition through correct diagnosis and treatment protocols? Not usually! But when it comes to discussing alcohol with a pregnant woman or the drinking habits of a mother whose child shows quite convincing signs of FASD – yes, I hear it often!

Unfortunately, there are no ‘right’ words. There is little anyone can do to ease the pain for a birth mother or any mother for that matter. There is no way to say the words that will hurt less, but they do have to be said – for the sake of the child, and, in the long term, the parents.

What also has to occur is a systemic and multi-disciplinary process of diagnosis, management, support and education. Existing services would be adequate if doctors at least could make a diagnosis of full FAS [where the facial anomalies, central nervous system dysfunction, confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure and growth deficiency make the diagnosis comparatively straightforward] and develop management strategies for these patients.

My family learned the hard way about this condition. Perhaps not surprisingly, having caused this unintentionally is of no consolation to me nor would it be to any mother who has felt her child move inside her and experienced the joy of holding her baby for the first time. Being a mother and hurting your baby are, for most women, mutually exclusive.

Nevertheless, this is something we will all have to deal with. I would go through it again a hundred times if necessary, if it meant that my sons could receive the assistance they need. This is not something a doctor needs to take on board to the extent where he or she believes that silence is the better option. Silence will never, ever be the better option with FASD.

Every teenager should be advised as a matter of course that drinking during pregnancy is harmful. No doubt it will cause fear and consternation if they are pregnant and have been drinking but it has to occur. I would have preferred to undergo the relatively minor concern of wondering what harm I had done by drinking a few drinks early on in my pregnancy, than by finding out when my children were teenagers that they had irreversible brain injury caused by drinking throughout my pregnancy.

There is another factor that is often overlooked − the birth of subsequent affected children. If a child is diagnosed subsequent children may not be affected. There would be many families whose children would now be healthy. Into their future would be woven the thread of peace and contentment, not fear and apprehension. And if only I had been one of these mothers, I would never have to see my son’s wide, terrified eyes – too scared to die but more afraid to live.

To my Doctor

‘Alcohol is a substance that is known to cause birth defects. If and when you chose to start a family, plan not to drink. If you are pregnant a

nd have been drinking, the sooner you stop, the healthier your baby will be. If you have trouble stopping, seek help.’

Developed by the Russell Family Fetal Alcohol Disorders Association as a community service

[1] http://alcoholthinkagain.com.au/Portals/0/documents/Alcohol percent20and percent20pregnancy percent20- percent20A percent20resource percent20for percent20health percent20professional s.pdf accessed on the 21st March 2015

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Information for Health Professionals – Telethon Institute for Child Health Research

Alcohol and Pregnancy Resources

The resources were developed to support health professionals address the issue of alcohol use in pregnancy with women. The following resources are available:

Booklet for Health Professionals

Fact Sheet for Health Professionals

The Alcohol and Pregnancy Resources for Health Professionals previously published and printed by the Telethon Institute for Child Health Research are now printed by the Drug and Alcohol Office. The content of these materials remains the same. Orders for the resources can be placed through the on-line publication order system – public access

There is no cost to order these materials.

Please refer to the following codes in the on-line publication order system:

ALCOHOL & DRUGS

Item Code DAO 005 Booklet for health professionals

Item Code DAO 006 Fact sheet for health professionals

Item Code DAO 007 Wallet card for women

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

RACGP Resource Library – Red Book

Guidelines for preventative activities in general practice 7th Edition

RACGP Resource Library – Green Book

RACGP Putting prevention into practice 2nd edition

RACGP Screening Tool

The RACGP Screening Tool of the 5 “A”s based on the ‘ask assess advise assist arrange’

RACGP SNAP (quit Smoking, betterNutrition, moderate Alcohol, morePhysical activity) Guidelines

SNAP: a population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice

Other Organisations

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing – Lifescripts

About Lifescripts and Pregnancy Resources

The Northern Division of General Practice Lifescripts Electronic Resources

Lifescripts Electronic Resources

Drug Education Network Resources

Prenatal Exposure to Alcohol (Pea) Prevention Handbook

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA)

FASD Resources – Flipchart and FASD Leaflet

Drug and Alcohol Services South Australia

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders; A Guide for Midwives

Genetics in Family Medicine: The Australian Handbook for General Practitioners

Perinatal Data Collection and Statistics

National Perinatal and Reproductive Epidemiology Research Unit

National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit

Congenital Conditions Register NSW

Queensland Perinatal Data Collection Unit

South Australia Pregnancy Outcomes Statistics Unit

Birth Defects Register South Australia

Victorian Birth Defects Register

Victorian Perinatal Data Collection Unit

WA Register of Developmental Anomalies